In April 2016, HTC released the Vive VR headset. Designed in conjunction with games developer Valve, the Vive represented a significant evolution in consumer Virtual Reality.

Technologically, the Vive’s breakthrough centred around a tracking system that could detect, within a 3x3x3m square volume, the position and orientation of the headset, controllers, and any other object that had a tracking puck attached to it. Crucially, this volumetric tracking ability was included as a default part of the basic kit.

The result, is that HTC’s hardware has effectively defined the minimum viable product for VR as “room scale” – an experience which lets you get out of the chair, and walk around within a defined area. Not only can you look out in all directions, you can physically circumnavigate a virtual object, as if it were a physical object sharing the room. When combined with Valve’s SteamVR platform and store, this has created an entire turnkey hardware and software ecosystem.

From my recent experience of them, the Vive plus Steam is a product, not a tech experiment. This is a tool, not a toy.

First, some basic terminology for the purposes of this article:

- XR: Extended / Extensible Reality – A blanket term covering all “reality” versions.

- VR: Virtual Reality – XR in which the real world is completely blocked out, and the user is immersed in a completely computer generated environment.

- AR: Augmented Reality XR in which the real world remains visible, directly or via camera feed, and computer generated elements are added, also known as “mediated reality”.

- GPU: Graphics Processing Unit – the part of a computer that does the work to generate the immersive environment.

- eGPU: A GPU in an external case, usually connected via Thunderbolt.

More than a year after the Vive’s release, Apple used their 2017 World Wide Developers Conference to announce they were bringing VR to macOS, in a developer preview form.

For those of us in the creative fields who are primarily Mac-based, and have wondered “when can I get this on my Mac?“, Apple’s announcement would seem to be good news. However, there are fundamental differences between Apple’s product philosophy for the Mac, and the needs of VR users and developers. This raises serious concerns as to the basic compatibility of Apple’s product and business model, with the rapidly evolving first decade of this new platform.

Hardware:

When it comes to Apple and VR, the screaming, clownsuit-wearing elephant in the room is this: Apple has weak graphics.

This is the overwhelming sentiment of everyone I have encountered with an interest in VR.

The most powerful GPU in Apple’s product range, AMD’s Vega 64 – with availability starting in the AU$8200 configuration of the iMac Pro, is a lowered-performance (but memory expanded) version of a card, which retails for around AU$800, and which is a fourth-tier product in terms of 3D performance, within the wider market.

Note: Adding that card to an iMac Pro, adds AU$960 to the price of the machine, whose price already includes the lower performance Vega 56. In contrast, the actual price difference between a retail Vega 56 and 64 is around AU$200. Effectively, you’re paying full price for both cards, even though Apple only supplies you with one of them.

The VR on Mac blog recent posted an article lamenting “Will we ever really see VR on the Mac?”, to which you can only respond “No, not in any meaningful sense, as long as Apple continues on its current product philosophy”.

To paraphrase Bill Clinton “It’s the GPUs, Stupid”.

When you’re looking at VR performance, what you’re effectively looking at, is the ability of the GPU to drive two high-resolution displays (one for each eye), at a high frame rate, with as many objects rendered at as high a quality as possible. Effectively, you’re looking at gaming performance – unsurprising, given a lot of VR is built on game engines.

Apple’s machines’ (discrete) GPUs are woefully underpowered, and regularly a generation out of date when compared to retail graphics cards for desktop computers, or those available in other brands of laptops.

Most of the presenters at Immerse were using macbooks for their slide decks, but none of the people I met use Apple gear, or seem to have any interest in using Apple gear to do VR, because, as I heard repeatedly, “the Mac has weak graphics”.

How weak is “weak”?

Looking at the GPUs available on the market, in terms of their ability to generate a complicated 3D environment, and render all the objects within that environment in high quality, at the necessary frame rate, here they are, roughly in order of performance, with a price comparison. This price comparison is important, because it represents not just how much it costs to get into VR if you already have a computer, but how much it costs, roughly on an annual schedule, to stay at the cutting edge of VR.

Note: This is excluding Pro GPUs like the Quadro, or Radeon Pro, since they are generally lower performance, in terms of 3D for gaming engines. The “Pro”-named GPUs in Apple’s products are gaming GPUs, and do not include error-correcting memory that is the primary distinguisher of “Pro” graphics cards.

- Nvidia Titan V: ~AU$3700. Although not designed as a gaming card, it generally outperforms any gaming card at gaming tasks.

- Nvidia Titan XP: AU$1950

- Nvidia 1080ti: ~AU$1100

- Nvidia 1080 / AMD Vega 64: $AU850 (IF you can get the AMD card in stock)

Realistically, the 1080ti should be considered the entry level for VR. Anything less, and you are not getting an environment of sufficient fidelity that it ceases to be a barrier between yourself, and the work. A 1080 may be a reasonable compromise if you want to do mobile VR in a laptop, but we’re not remotely close to seeing a Vega 64 in a Mac laptop.

So what does this mean?

- The highest-spec GPU in Apple’s “VR Ready” iMac Pro is a 4th-tier product, and is below the minimum spec any serious content creator should consider for their VR workstation. It’s certainly well below the performance that your potential customers will be able to obtain in a “Gaming PC” that costs a quarter of the price of your “Workstation”.

- The GPU in the iMac Pro is effectively non-upgradable. The AU$8-20k machine you buy today will fall further behind the leading edge of visual fidelity for VR environments every year. A “Gaming PC” will stay cutting edge for around AU$1200 / year.

- While Vega 64 is roughly equivalent in performance to Nvidia’s base 1080 (which is significantly lower performance than the 1080ti), in full-fat retail cards, it can require almost double the amount of electricity needed to power the 1080.

- Apple’s best laptop GPU, the Radeon 560 offers less than half the gaming 3D performance (which again, is effectively VR equivalent) of the mobile 1080, and you can get Windows laptops with dual 1080s in them.

- Apple is not providing support as yet, for Nvidia cards in eGPU enclosures, and so far only officially supports a single brand and model of AMD card – the Sapphire Radeon RX580 Pulse, which is not a “VR Capable” GPU by any reasonable definition.

The consequences of this are significant.

We’re not going to see performance gains in GPU hardware, and performance requirements for VR plateau any time in the near future. A decade ago, computers were fast enough to do pretty much anything in print production – 300dpi has remained the quality of most print, and paper sizes haven’t changed. That’s not going to happen for VR in the next decade.

GPU progress is not going to hold itself to Apple’s preferred refresh and repurchase cycles for computers. The relationship content producers have with GPUs is, I suspect, going to be similar to the relationship iOS developers have with iPhones & iPads – whatever the top of the range is, they’ll need to have it as soon as it’s released. People aren’t going to turn over a several thousand dollar computer every year, just to get the new GPU.

By Apple’s own admission at WWDC, eGPU is a secondrate option, as compared to a GPU in a slot on the motherboard. A slotted card on the motherboard has potentially four times the bandwidth of a card in an external enclosure. For a user with an 11-13″ microlight laptop, eGPU is a good option to have VR capability at a desk, but it’s not a good solution for desktop computers, or for portable VR.

While Nvidia’s mobile 1080 has been an option in PC laptops for some time now, and offers performance comparable to its full-fat desktop version, AMD (and by extension Apple) seems to have nothing comparable (a mobile Vega 64) on the horizon for Macbooks.

There are, therefore, some really serious questions that need to be asked about the priorities of Apple in using AMD for graphics hardware. Overall, AMD tends to be marginally better for computational GPUs, in other words, GPUs that are used for non-dislay purposes. For realtime 3D environments, Nvidia is significantly ahead, and in mobile, represents having the capability to to VR at all.

If the balance of computation vs 3D “gaming” performance means computation is faster, but VR isn’t possible, then it really starts to feel like back in the days when the iMac went with DVD-ROM while everyone else was building around CD burners.

Software:

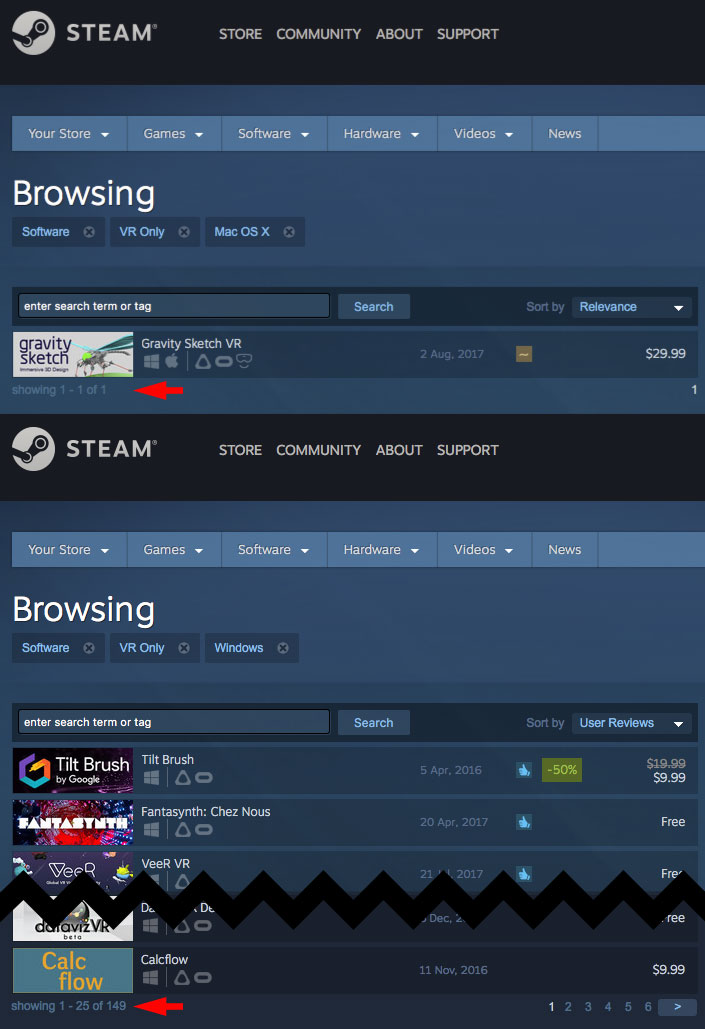

Apart from operating system system changes relating to driving the actual VR hardware, Apple’s “embrace of VR” was more or less devoid of content on Apple’s part, in terms of tools for users.

Apple’s biggest announcement regarded adding “VR support” to Final Cut Pro X. As far as I can see, this is about 360 video, not VR. This needs to emphasised – 360 Video is not VR. It shares some superficial similarities, but these are overwhelmed by the fundamental differences:

- 360 Video is usually not 3D. It’s effectively just video filling your field of vision.

- 360 Video is a passive medium. While you can look around, you can’t interact with the environment, or move your viewpoint from a fixed location.

In contrast, VR is:

- a place you go to,

- a place you move about in, and

- a place where you do things.

VR is an activity environment, 360 Video is television in which you can only see one third of what is happening, at any one time.

The power of VR is what you can do in it, not what you can see with it.

For example Tvori:

And for a more nuts & bolts vision of actually working in VR:

This is using a 3D VR workspace to create content that will be played on a 2D screen.

This is important – the future of content creation when it comes to VR is NOT going to be based upon using flat screens to create content that can then be viewed on VR goggles. It’s the other way around – we’re going to be using VR toolsets to make content that will be deployed back to 2D platforms.

All of the current development and deployment environments are inherently cross-platform. It’s unlikely that anyone is going to be making macOS-specific VR apps any time in the near future. That’s a self-evident reality – the install base & market for VR-capable Macs is simply too small, and the install base & market for VR-capable PCs too large, to justify not using an application platform that allows for cross-platform applications. VR does not have the problem of a cross-platform app feeling like a secondrate, uncanny-valley facsimile of a native application. In VR, the operating system conveys no “native” UI paradigms, it’s just a launcher, less in fact given that Steam and Viveport handle launching and management of apps – it’s a glorified BIOS.

This is not going to be a replay of iOS, where Apple’s mobile products were undeniably more powerful, and more capable than the majority of the vastly larger market of Android and Windows Mobile devices, and were therefore able to sustain businesses that could ignore other platforms. VR-capable Macs are smaller in market, less-capable as devices due to weak graphics, higher in price to buy, and radically higher in price to maintain relative performance, than VR-capable PCs. As long as this is the case, the Mac will be begging for scraps at a VR table, where Windows (and eventually Linux & SteamOS) will occupy the seats.

The inherent cross-operating-system metaplatform nature of Steam reflects a growing trend within the Pro software market – formerly Mac-only developers are moving their products to be cross-platform, in effect, making their own technologies the platform, and relegating macOS or Windows to little more than a dumb pipe for commoditised hardware management.

One of the recent darlings of the Apple world, Serif, has taken their Affinity suite of design, imaging and publishing apps across to Windows, as have Macphun, who’ve renamed themselves Skylum, and shifted their photography software cross-platform. In the past, developers had marketed their products, based on the degree to which they had embraced Apple’s in-house technologies as the basis of their apps – how “native” their apps were. These days, more and more are emphasising independence from Apple’s technology stack. The presence of the cross-platform lifeboat is becoming more important to customers of Pro apps, than any advantage brought by being “more native”. The pro creative market, by and large, is uncoupling its financial future from Apple’s product strategy. In effect, it’s betting against that strategy.

What does Apple, a company whose core purpose is in creating tasteful, consistent user interface (however debatable that might be these days), have to offer in a world where user environments are the sole domain of the apps themselves, and the operating system is invisible to the user?

Thought exercise, Apple & Gaming:

Video and cinema has always been considered a core market in which Apple had to invest. Gaming (on macOS) has always been a market that Apple fans have been fine with Apple ignoring. The argument has always been about the economics and relative scale of each. It’s worth bearing in mind however, that the size of the games market and industry dwarfs the cinema industry.

Why is it ok amongst Apple fans, Apple-centric media, and shareholders, for Apple to devote resources to making tools for moviemakers / watchers rather than directing it at game developers / players?

When Apple cuts a product, or restricts the versatility of a product under the guise of “focus” there’s no end of people who’ll argue that Apple is focussing on where the profits are. Mac sales are relatively stagnant year over year. Gaming PCs, or as they’d be called if Apple sold them “VR Workstations” have been consistently growing in sales of around 25% year upon year for a while now.

Windows’ gaming focus and games ecosystem, is co-evolutionary with VR. It is the relentless drive to make Windows as good as possible as a gaming platform, that makes it the better VR platform. No amount of optimisation Apple can do with Metal, their 3D infrastructure, can make up for the fact that they’re shipping sub-standard GPUs in their devices.

”High spirits are just no substitute for 800 rounds a minute!”

Apple’s WWDC VR announcements seem to have had very little impact on people who are using, and making with VR now. Noone I spoke to at Immerse seemed particularly excited about the prospect of Apple getting into the space, or seemed to think Apple had anything in particular to offer. If you look at what Apple did to professional photographers by neglecting, and then dumping their Aperture pro photo management solution, without providing a replacement (and no, Photos is not that), that wariness is well-justified.

What Immerse really opened my eyes to, is that VR is very probably a black swan for Apple, who have spent the last 5 years eliminating the very thing that is central to powering VR – motherboard PCI slots, the associated retail-upgradble GPU, and the entire culture of 3D performance focus, from their product philosophy.

VR is an iceberg, and Apple, no matter how titanic, will not move it. The question is whether the current design, engineering and marketing leadership, who have produced generation upon generation of computers that sacrifice utility and customer-upgradability in the pursuit of smallness, are culturally capable of accepting that fact.

Hey, If you liked reading this, maybe you’d like to donate?