The 2018 production of Rent at QPAC, I produced a large suspended sculpture that formed a feature piece in the set.

The 2018 production of Rent at QPAC, I produced a large suspended sculpture that formed a feature piece in the set.

Exhibited Works:

- BØN541 v3.0

Pinned and chronological feed of posts. Check The State of The Art for the big picture.

I’ve finally succeeded in getting my Urban Exploration / Urban Landscape photography kit together, so I thought I’d document it here.

The goal was to have a single backpack that I could travel with, which didn’t scream “tactical gear bag”, and which could handle a versatile photographic load.

Peak Design Everyday Backpack 20L, with:

Nikon d8XX with the 14-24 2.8, with a modified 3 Legged Thing QR-11 L-Plate. Umbrella in side pocket. Headphones and small medikit with hand sanitiser, paracetamol etc. Godox V860II & X1-n. Blackrapid Sport Breathe. GSI low-profile water battle in side pocket. 3 Legged Thing Leo with Airhed Switch.

It all packs in very snug, and there’s some modifications to the dividers to scavenge every last millimetre in width across the bag (not such a big commitment now they sell them separately). There’s also lens tissues, lens covers, remote release cable, camping knife-spork and a couple of cable adapters in the interior side pockets. Wallet and a protein bar in the top compartment, and still space for an iPad in the laptop sleeve.

Inside, there’s one vertical divider at the bottom to separate the camera onto the left, and tripod on the right, then one horizontal divider across the top of that.

The horizontal is folded up on the right to make one tall space for the tripod on the right. One layer of the folded up part on the horizontal divider is removed to give 5-10mm more room in the top left compartment. The vertical divider has a layer removed from the folding section as well, to give more room to the L-Plate on the camera, so as to stop the grip from poking out through the side. That vertical divider also has an extra row of velcro sewn onto it, so the whole side adheres to the inner surface of the bag, rather than just the stock tab. The Blackrapid bag packs in behind the tripod in the space it creates where the carbon fibre of the legs is exposed. The trimmed parts removed from the folding sections of the dividers are velcro-ed into the bottom of the bag with adhesive-backed velcro strips, to provide a bit of padding for the lens and bottom of the tripod.

If this article was of use, a donation would help support my projects.

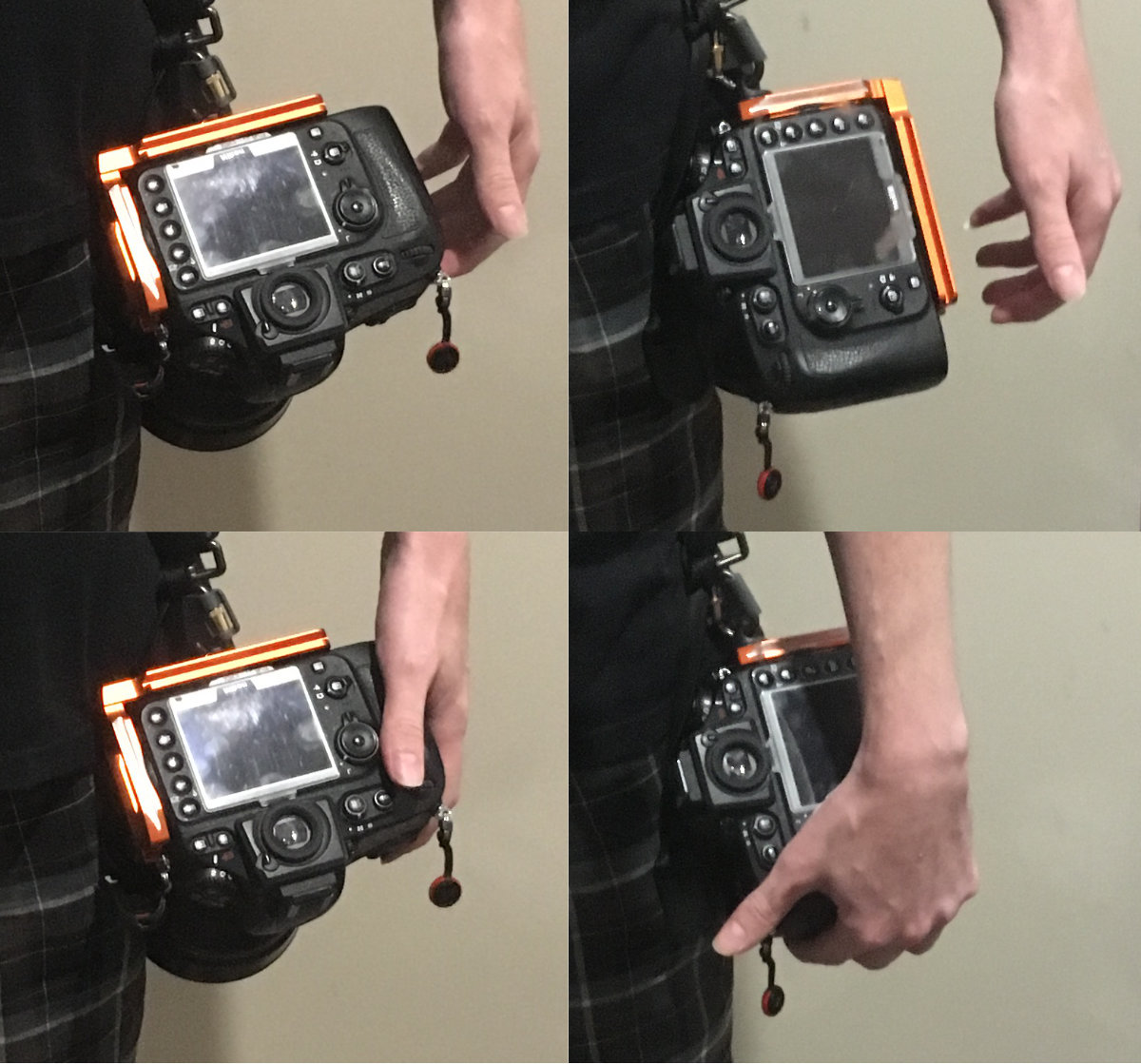

Here’s a gear hack to combine two products that should play well together, but don’t. The Blackrapid FR-T1 connector, and 3 Legged Thing QR-11 L-Bracket.

Technically, the QR-11 does work with Blackrapid straps – there’s a 1/4″ mounting hole in the short arm to screw in a Connector, however this interferes with the ability of the short arm’s rail to mount in the Tripod’s Arca clamp. Also, the ergonomics don’t work as well when the camera is hanging on the strap.

As a bonus, here’s a modification of the short arm on the L-Plate, to get it as close as possible against the side of the camera.

Material needs to be removed to clear the rubber gasket covers for the ports on the front of the camera, as well as the thumbnail catch for the port door on the side.

If this article was of use, a donation would help support my projects.

In April 2016, HTC released the Vive VR headset. Designed in conjunction with games developer Valve, the Vive represented a significant evolution in consumer Virtual Reality.

Technologically, the Vive’s breakthrough centred around a tracking system that could detect, within a 3x3x3m square volume, the position and orientation of the headset, controllers, and any other object that had a tracking puck attached to it. Crucially, this volumetric tracking ability was included as a default part of the basic kit.

The result, is that HTC’s hardware has effectively defined the minimum viable product for VR as “room scale” – an experience which lets you get out of the chair, and walk around within a defined area. Not only can you look out in all directions, you can physically circumnavigate a virtual object, as if it were a physical object sharing the room. When combined with Valve’s SteamVR platform and store, this has created an entire turnkey hardware and software ecosystem.

From my recent experience of them, the Vive plus Steam is a product, not a tech experiment. This is a tool, not a toy.

First, some basic terminology for the purposes of this article:

More than a year after the Vive’s release, Apple used their 2017 World Wide Developers Conference to announce they were bringing VR to macOS, in a developer preview form.

For those of us in the creative fields who are primarily Mac-based, and have wondered “when can I get this on my Mac?“, Apple’s announcement would seem to be good news. However, there are fundamental differences between Apple’s product philosophy for the Mac, and the needs of VR users and developers. This raises serious concerns as to the basic compatibility of Apple’s product and business model, with the rapidly evolving first decade of this new platform.

When it comes to Apple and VR, the screaming, clownsuit-wearing elephant in the room is this: Apple has weak graphics.

This is the overwhelming sentiment of everyone I have encountered with an interest in VR.

The most powerful GPU in Apple’s product range, AMD’s Vega 64 – with availability starting in the AU$8200 configuration of the iMac Pro, is a lowered-performance (but memory expanded) version of a card, which retails for around AU$800, and which is a fourth-tier product in terms of 3D performance, within the wider market.

Note: Adding that card to an iMac Pro, adds AU$960 to the price of the machine, whose price already includes the lower performance Vega 56. In contrast, the actual price difference between a retail Vega 56 and 64 is around AU$200. Effectively, you’re paying full price for both cards, even though Apple only supplies you with one of them.

The VR on Mac blog recent posted an article lamenting “Will we ever really see VR on the Mac?”, to which you can only respond “No, not in any meaningful sense, as long as Apple continues on its current product philosophy”.

To paraphrase Bill Clinton “It’s the GPUs, Stupid”.

When you’re looking at VR performance, what you’re effectively looking at, is the ability of the GPU to drive two high-resolution displays (one for each eye), at a high frame rate, with as many objects rendered at as high a quality as possible. Effectively, you’re looking at gaming performance – unsurprising, given a lot of VR is built on game engines.

Apple’s machines’ (discrete) GPUs are woefully underpowered, and regularly a generation out of date when compared to retail graphics cards for desktop computers, or those available in other brands of laptops.

Most of the presenters at Immerse were using macbooks for their slide decks, but none of the people I met use Apple gear, or seem to have any interest in using Apple gear to do VR, because, as I heard repeatedly, “the Mac has weak graphics”.

Looking at the GPUs available on the market, in terms of their ability to generate a complicated 3D environment, and render all the objects within that environment in high quality, at the necessary frame rate, here they are, roughly in order of performance, with a price comparison. This price comparison is important, because it represents not just how much it costs to get into VR if you already have a computer, but how much it costs, roughly on an annual schedule, to stay at the cutting edge of VR.

Note: This is excluding Pro GPUs like the Quadro, or Radeon Pro, since they are generally lower performance, in terms of 3D for gaming engines. The “Pro”-named GPUs in Apple’s products are gaming GPUs, and do not include error-correcting memory that is the primary distinguisher of “Pro” graphics cards.

Realistically, the 1080ti should be considered the entry level for VR. Anything less, and you are not getting an environment of sufficient fidelity that it ceases to be a barrier between yourself, and the work. A 1080 may be a reasonable compromise if you want to do mobile VR in a laptop, but we’re not remotely close to seeing a Vega 64 in a Mac laptop.

The consequences of this are significant.

We’re not going to see performance gains in GPU hardware, and performance requirements for VR plateau any time in the near future. A decade ago, computers were fast enough to do pretty much anything in print production – 300dpi has remained the quality of most print, and paper sizes haven’t changed. That’s not going to happen for VR in the next decade.

GPU progress is not going to hold itself to Apple’s preferred refresh and repurchase cycles for computers. The relationship content producers have with GPUs is, I suspect, going to be similar to the relationship iOS developers have with iPhones & iPads – whatever the top of the range is, they’ll need to have it as soon as it’s released. People aren’t going to turn over a several thousand dollar computer every year, just to get the new GPU.

By Apple’s own admission at WWDC, eGPU is a secondrate option, as compared to a GPU in a slot on the motherboard. A slotted card on the motherboard has potentially four times the bandwidth of a card in an external enclosure. For a user with an 11-13″ microlight laptop, eGPU is a good option to have VR capability at a desk, but it’s not a good solution for desktop computers, or for portable VR.

While Nvidia’s mobile 1080 has been an option in PC laptops for some time now, and offers performance comparable to its full-fat desktop version, AMD (and by extension Apple) seems to have nothing comparable (a mobile Vega 64) on the horizon for Macbooks.

There are, therefore, some really serious questions that need to be asked about the priorities of Apple in using AMD for graphics hardware. Overall, AMD tends to be marginally better for computational GPUs, in other words, GPUs that are used for non-dislay purposes. For realtime 3D environments, Nvidia is significantly ahead, and in mobile, represents having the capability to to VR at all.

If the balance of computation vs 3D “gaming” performance means computation is faster, but VR isn’t possible, then it really starts to feel like back in the days when the iMac went with DVD-ROM while everyone else was building around CD burners.

Apart from operating system system changes relating to driving the actual VR hardware, Apple’s “embrace of VR” was more or less devoid of content on Apple’s part, in terms of tools for users.

Apple’s biggest announcement regarded adding “VR support” to Final Cut Pro X. As far as I can see, this is about 360 video, not VR. This needs to emphasised – 360 Video is not VR. It shares some superficial similarities, but these are overwhelmed by the fundamental differences:

In contrast, VR is:

VR is an activity environment, 360 Video is television in which you can only see one third of what is happening, at any one time.

The power of VR is what you can do in it, not what you can see with it.

For example Tvori:

And for a more nuts & bolts vision of actually working in VR:

This is using a 3D VR workspace to create content that will be played on a 2D screen.

This is important – the future of content creation when it comes to VR is NOT going to be based upon using flat screens to create content that can then be viewed on VR goggles. It’s the other way around – we’re going to be using VR toolsets to make content that will be deployed back to 2D platforms.

All of the current development and deployment environments are inherently cross-platform. It’s unlikely that anyone is going to be making macOS-specific VR apps any time in the near future. That’s a self-evident reality – the install base & market for VR-capable Macs is simply too small, and the install base & market for VR-capable PCs too large, to justify not using an application platform that allows for cross-platform applications. VR does not have the problem of a cross-platform app feeling like a secondrate, uncanny-valley facsimile of a native application. In VR, the operating system conveys no “native” UI paradigms, it’s just a launcher, less in fact given that Steam and Viveport handle launching and management of apps – it’s a glorified BIOS.

This is not going to be a replay of iOS, where Apple’s mobile products were undeniably more powerful, and more capable than the majority of the vastly larger market of Android and Windows Mobile devices, and were therefore able to sustain businesses that could ignore other platforms. VR-capable Macs are smaller in market, less-capable as devices due to weak graphics, higher in price to buy, and radically higher in price to maintain relative performance, than VR-capable PCs. As long as this is the case, the Mac will be begging for scraps at a VR table, where Windows (and eventually Linux & SteamOS) will occupy the seats.

The inherent cross-operating-system metaplatform nature of Steam reflects a growing trend within the Pro software market – formerly Mac-only developers are moving their products to be cross-platform, in effect, making their own technologies the platform, and relegating macOS or Windows to little more than a dumb pipe for commoditised hardware management.

One of the recent darlings of the Apple world, Serif, has taken their Affinity suite of design, imaging and publishing apps across to Windows, as have Macphun, who’ve renamed themselves Skylum, and shifted their photography software cross-platform. In the past, developers had marketed their products, based on the degree to which they had embraced Apple’s in-house technologies as the basis of their apps – how “native” their apps were. These days, more and more are emphasising independence from Apple’s technology stack. The presence of the cross-platform lifeboat is becoming more important to customers of Pro apps, than any advantage brought by being “more native”. The pro creative market, by and large, is uncoupling its financial future from Apple’s product strategy. In effect, it’s betting against that strategy.

What does Apple, a company whose core purpose is in creating tasteful, consistent user interface (however debatable that might be these days), have to offer in a world where user environments are the sole domain of the apps themselves, and the operating system is invisible to the user?

Video and cinema has always been considered a core market in which Apple had to invest. Gaming (on macOS) has always been a market that Apple fans have been fine with Apple ignoring. The argument has always been about the economics and relative scale of each. It’s worth bearing in mind however, that the size of the games market and industry dwarfs the cinema industry.

Why is it ok amongst Apple fans, Apple-centric media, and shareholders, for Apple to devote resources to making tools for moviemakers / watchers rather than directing it at game developers / players?

When Apple cuts a product, or restricts the versatility of a product under the guise of “focus” there’s no end of people who’ll argue that Apple is focussing on where the profits are. Mac sales are relatively stagnant year over year. Gaming PCs, or as they’d be called if Apple sold them “VR Workstations” have been consistently growing in sales of around 25% year upon year for a while now.

Windows’ gaming focus and games ecosystem, is co-evolutionary with VR. It is the relentless drive to make Windows as good as possible as a gaming platform, that makes it the better VR platform. No amount of optimisation Apple can do with Metal, their 3D infrastructure, can make up for the fact that they’re shipping sub-standard GPUs in their devices.

”High spirits are just no substitute for 800 rounds a minute!”

Apple’s WWDC VR announcements seem to have had very little impact on people who are using, and making with VR now. Noone I spoke to at Immerse seemed particularly excited about the prospect of Apple getting into the space, or seemed to think Apple had anything in particular to offer. If you look at what Apple did to professional photographers by neglecting, and then dumping their Aperture pro photo management solution, without providing a replacement (and no, Photos is not that), that wariness is well-justified.

What Immerse really opened my eyes to, is that VR is very probably a black swan for Apple, who have spent the last 5 years eliminating the very thing that is central to powering VR – motherboard PCI slots, the associated retail-upgradble GPU, and the entire culture of 3D performance focus, from their product philosophy.

VR is an iceberg, and Apple, no matter how titanic, will not move it. The question is whether the current design, engineering and marketing leadership, who have produced generation upon generation of computers that sacrifice utility and customer-upgradability in the pursuit of smallness, are culturally capable of accepting that fact.

Hey, If you liked reading this, maybe you’d like to donate?

So, 2017. It’s been a year of ups and downs. More downs than ups, but that gives 2018 a lot more room to improve.

My knee had a setback this year, but is slowly on the mend after a visit to a surgeon who suggested a new exercise regime.

I had a change in an immuno-modulating medication, from requiring an injection every second day for the past 12 years, to one every 2 weeks. So that’s a pretty significant improvement.

I was able to catch up with two of my dear friends in Melbourne this year. As nice as it was to see them, I was down to visit my father who’s battling cancer, so the trips were tinged with melancholy.

I still miss all my peeps in Sydney (and the amazing gozlame at Marrickville Markets). As nice as Noosa is, it’s somewhat isolating if your thing isn’t surfing. I’ve been going to a few meetups in the sunshine coast area for people interested in VR & video game development, I might just have to get used to travelling to neighbouring towns a bit more, which I did a fair bit of this year, taking day-trips out to various small towns in the area.

I balance that against the sheer natural beauty of this area. Earlier in the year, after driving 5 minutes from home, I was able to see humpback whales – an adult and a calf that had been overnighting in the bay. I didn’t have to go out in a boat, just walked a few steps from where we parked the car. I was able to see all kinds of marine life walking to the river at the end of my street. On Christmas day we had ducks from the river wandering about in our driveway.

We were also hit by the tail end of a cyclone, which was interesting. You get a real glimpse into the heavy-weather future here.

I saw a bunch of interesting performances this year, standup comedy by Jimoin, an amateur musical version of Jurassic Park, a live performance of the British podcast My Dad Wrote a Porno, Damian Cowell’s Disco Machine, and while I was in Melbourne, a trip to the NGV to see a big Hokusai retrospective.

There’s a little rant building there, because this trip to Melbourne made me see a side of that city I’ve never felt before – an unjustified self-importance that manifests in a reflexive need to tell tourists from other parts of Australia that they’re finally going to be able to get some (cultural item), now they’re in Melbourne. The simple truth is that there’s nothing in Melbourne, not culture, not food, not interesting little bars, that can’t be found anywhere else with better weather. The NGV in particular, has a stupid “no professional cameras” policy, which means they try to stop you taking a DSLR into exhibitions. If a publicly funded gallery isn’t supposed to be a place for artists to investigate and document works of art, just what is its function?

I spent more time in Brisbane this year, and have developed a real affection for it as a city. It’s not crowded in the way that Sydney and Melbourne are, and the multitude of radically different bridges over the river, give it a quirkiness I dig.

A big event this year was an attempt to get one of my sculptures installed on the grounds of the local Men’s Shed. This was a significant professional undertaking, involving coordinating with the Men’s Shed leadership, and the local water utility who own the land. I photographed the site, created a pitch document showing how an unused scrap of land would be made into a feature for the entrance to the site, and laid out how it would all be done at no cost to either organisation. Everyone seemed quite keen, then the water utility told me that someone in the Men’s Shed leadership, who had been away when I was conducting initial meetings, had told them that the Men’s Shed wouldn’t be supportive of the proposal if it came up to a vote amongst their leadership. That’s left a bit of a bad taste in my mouth.

I continued to shoot photos throughout the year, my camera being one of the few creative instruments available in an absence of studio space. Updates for Surfing The Deathline came out, to a point at which all the niggling little issues I had with some of the older artwork appear to have been fixed. I also signed up for a TIG welding course, which will begin in February 2018, and should allow me to get my metal sculpture mojo back. It’s much neater, and can potentially be done at home, than the MIG process I’ve used previously.

The most effecting artistic endeavour this year however, goes to my first experience of freestanding VR.

VR is my new religion, it’s where I want to spend my computing time. Drawing and painting in a three dimensional environment is so profound, it left me almost in tears. Hand in hand with this, is a profound loss of faith in the ability of Apple to keep providing products I want to use. I’ve written about what a bad fit Apple’s hardware model is for VR, which requires regular user-upgrades of graphical hardware, but I add to that that nothing from Apple has improved my enjoyment of using their devices in the last couple of years – quite the opposite, every update they make, makes the products less reliable, less pleasant to use, and breaks compatibility with other products, forcing you onto this never-ending merry-go-round of upgrades, so that you never have a stable set of systems where everything works together. I’m left asking myself “what do I actually get from paying a premium for Apple gear, if it’s not any more stable, or pleasant to use than the alternative?”. More than the implementation, I find myself increasingly dissatisfied with the philosophy behind Apple’s products – more and more, these are products which reflect the decision-making people who create them – inhumanly wealthy, able-bodied people with unlimited bandwidth. That’s not me, and increasingly, Apple’s products are losing the ability to serve anyone who doesn’t want to sign up for a world of sealed, non-upgradable appliances, where the software is always a semi-functional work in progress.

It may be that my future is in Windows or Linux workstations, especially since all my professional software is cross platform these days.

The really big tech thing this year has been the arrival of the NBN where I live. We’ve gone from the fastest possible connection we could get – 7/1 (down/up), which would flake out and fail whenever we had sustained rain, to 107/44 which has been rock solid through the worst of weather. We also ditched our previous provider, Telstra, for a small company, who, for the same price, don’t offer any “unlimited” plans, so peak hour congestion is largely unnoticeable. Next to my change of medication, knowing I’ll never have to speak to one of Telstra’s “support” people ever agin, is one of the happiest changes this year has brought.

In photography, I finally bought a speedlight – something I’ve wanted for a while now, so that I could have lighting while I’m out and about. It’s an interesting piece of ahead-of-the-curve technology, using a lithium-ion battery rather than AAs, and having the ability to be driven wirelessly.

Closing out the year, I finally bought a travel tripod from a company I’ve been following for a number of years. They’re another small outfit, who try to engineer their way into punching above their weight. It hasn’t been delivered yet, but hopefully it’ll get here soon, and I’ll be free to do a bit more photography-oriented hiking.

So, that’s 2017 in a nutshell.

Some terminology for the purposes of this article:

A few weeks ago, here in the sticks of regional Australia, we had a little conference day (immerseconf), with internationally practicing artists from all over the country (including the head of HTC Vive in Australia), demoing how various forms of Extended Reality are being used by artists to create content.

Interestingly, while there was a “serious games” (training & education simulations) discussion, traditional entertainment videogames weren’t covered – this was a conference targeted at makers, and the toolsets available to them for creating. This shouldn’t be taken as indicating the experience was dull – delight and joy are inherent to the experience of doing work in VR.

I’ve been reading about and waiting for this tech since the 1980s. Last time I tried it a couple of years ago, the head-mounted display (goggles) was an Oculus devkit, and interaction was via a playstation controller.

I was ill within a minute.

A theory of why this happens, is that it’s a result of lag between moving your head, and seeing the corresponding movement of the virtual world through the goggles. With the Vive, that problem is solved – the viewpoint is stuck fast to your proprioceptive experience of movement. Lag is gone, you are there.

For an artist, the experience of VR marks a division between everything you have done, learned or experienced in art-making prior, and what you are to do afterwards. It is as redefining an experience as postulated in Crosley Bendix’s discussion of the “discovery” of the new primary colour “Squant”.

In my life, I have been literally moved to tears once by a work I saw in an exhibition – Picasso’s “Head of a Woman”. Why? I had studied this work, part of the canon of historically important constructed sculpture, for years at art school. I’d written essays concerning, and answered slide tests about it. However, every photo I had seen was in black and white. I finally saw it in the flesh at an exhibition, and out of nowhere found myself weeping at the fact that I had never known what colour it was painted. Nothing I had read, or studied, prepared me for the overwhelming emotional impact of meeting it, face to face, and realising that I had not known something as fundamental as its colour.

Of all the great leaps in art making that Picasso was personally involved with, it was his collaboration with Julio González that more or less invented welded steel sculpture. He did this, primarily out of a desire to be able to “take a line for a walk” in three dimensions, to draw with thin metal rod, the only material whose structural strength could span distance without thickness or sagging.

In VR, free-standing, able to walk about with multi-function hand controllers in an entirely simulated, blank environment, I was once again almost in tears at how profound the experience of this tech is for artmaking. One can literally take a line for a walk, twist it, loop it around itself, trace out the topology of knots, zoom out, zoom inside, and see that three dimensional drawing as a physical object, hanging in the air.

The tools I played with were from Google – Blocks, a simple 3d modelling program, and Tilt Brush, a drawing and painting program (which is also a 3d modeller – it just models paint strokes, and so produces flat ribbons of paint, that follow the 3D orientation of the controller when you make them). They’re reasonably primitive compared to traditional 2D painting and modelling apps, but there’s clearly a commercial space for selling tools for VR.

Just watch this. That’s the actual experience of creating and working in Tilt Brush.

Or this:

Why would you want to use a screen-based 3d modeller?

There is a school of opinion which holds that AR is the “good” version of XR, that VR is a niche for games, that the goggles etc required for immersion makes VR inherently not a thing for the everyperson.

I have a different take on that. I think that AR would seem to be the “good” version of XR, vs full immersion VR, if you’re the sort of person whose socioeconomic status means your life is the sort of life from which you would never want to seek an escape. AR is lovely, if you’re able-bodied, rich, have a nice house, and a job with sufficient seniority that you have your own office and can shut out distraction.

In other words, if you’re employed with any sort of decision-making authority at a large tech company.

If you live in a tiny apartment or room in a sharehouse, or have a disability whose profundity stops you going out to access experiences, or work in a place where you can’t tune out visual distraction, in other words, if your life isn’t already the sort of 1%er fantasy that most people would like to escape to, then perhaps AR isn’t that compelling in comparison.

From that perspective, AR that does not have a “shut out the real world” function isn’t a complete solution – it’s not the whole story.

By the way, saying the goggles are inconvenient – go speak to anyone who does any sort of manual trade work. VR goggles are no more inconvenient than having to wear safety glasses, gloves, steel-capped boots, ear muffs, a respirator, or welding helmet. Just because it’s less convenient than an office worker is used to, doesn’t mean a lot – if I can sketch in 3d before I go out into the welding bay, that’s a huge convenience factor.

My encounter with Vive leaves me with mixed emotions. I am absolutely going to be gearing up for VR. You simply can’t try this tech, and then not move to make art with it. VR is here, and it is now. It is a complete, usable product with both entertainment, and work tools, not an early-access developer preview.

A lot of the coverage I’ve seen of VR, from people who perhaps don’t understand the sheer amount of heavy lifting necessary to drive the experience, centres around ideas like “wait until the PC isn’t required“. That isn’t going to happen, or rather, that’s going to be a sub-standard experience – a better packaging of current smartphone-based VR. The PC to drive VR isn’t going to go away, because the progress to be made in the medium, the complexity and graphical fidelity has so much room for growth that enthusiasts will keep asking for more, and content creators will have to keep up in order to feed that cycle.

Local Australian pricing has the Vive setup for about a thousand dollars, an Nvidia 1080ti for about another thousand, but what to do for a computer to run that rig?

Does Apple have a solution that lets me stay on the Mac, or do I jump to Windows, and begin the inevitable migration of all my Pro software (which is niche enough that it HAS to be cross platform) and production processes across to Windows versions?

Read on in Part 2: Hard Reality

Hey, If you liked reading this, maybe you’d like to donate?

An experiment with trying a Little Planet using a very short depth of field, so that only the dead centre is in hard focus. Like a lot of artistic experiments, it’s a bit of a failure, that teaches towards success. What it demonstrates to me is that it’s the crispness of everything at the “horizon” of the image that gives Little Planet projections their special appeal.

A couple of years after writing this, I found the officially sanctioned way of doing what I’m doing here. It’s based on the Time Machine command-line utilities. I’ve used it since, and it works well.

Here it is: https://www.baligu.com/pondini/TM/B6.html

If you want to see what’s happening while time machine is doing its run, you can try this from the command line:

log stream –style syslog –predicate ‘senderImagePath contains[cd] “TimeMachine”‘ –info

Anyway, back to the original article:

…or, how to make Time Machine treat a duplicated and enlarged source volume as the original, and continue incremental backups.

It’s not supposed to be possible, but after 3 days of research, and multiple 4-8 hour backup sessions, I’ve cracked it – done something that, as far as I can tell, noone else believes can be done, or has documented how to do. If you follow the instructions here, using only free tools, you’ll be able to do it as well.

You have a Time Machine drive handling backup for multiple drives attached to your system. For example:

Boot / User: 500gb, Photos: 900GB.

Right now, your Time Machine backup is around 1.4TB minimum. On a 2TB drive, that leaves you with 600GB for historical versions of files. Every time you change a file in any way, another copy of the file is added to the Time Machine volume.

Let’s assume your Photos drive is 1TB, and you need to move the contents onto a larger drive before it runs out of space.

You plug in a new 2TB drive, format it with the same name, copy the contents of the Photos drive across, remove the old Photos drive.

You let Time Machine do its thing.

Time Machine will treat the new 2TB Photos drive as a different drive from the original, and perform a full backup of the drive, even though the data on it is identical in every way. Using Carbon Copy Cloner, or Disk Utility’s Restore function will not get around this.

Your Time machine storage now requires: Boot / User: 500GB, Photos (old): 900GB, Photos (new): 900GB, for a total of 2300GB. You’ve now got a backup that’s larger than your 2TB Time Machine volume, and importantly, Time Machine will delete all your historical backups in order to make room for what will effectively be two identical copies of most of your photos.

This happens because Time Machine uses the UUID of the drive to identify it. The UUID is assigned to the drive when it is formatted in Disk Utility, it’s effectively random, and is unaffected by changes to the name of a drive. This means you can change the name of your drive without triggering a full backup, it also means the integrity of your Time Machine backups can’t be effected by temporarily plugging in another drive of the same name, even if the contents are mostly identical.

In general, it’s a safety feature, but as above, it has a serious drawback.

In order to make the enlarged drive behave as a continuation of the old one, you have to fool Time Machine into thinking the new drive is the old one. To do this, you have to copy the data correctly, alter the new drive’s UUID to match the original, then alter the original drive’s UUID so it doesn’t conflict.

Note: this is how I made it work – some stuff here may not be totally necessary, but as anyone who used SCSI back in the day knows, superstition is an important part of technology.

cd <drag the "MacOS" title icon in the titlebar of the window to here> <hit enter>

./SDDiskTool -g <drag old Photos source disk from Finder> <enter>

sudo ./SDDiskTool -s <paste the encoded uuid> <drag new Photos target disk from Finder> <enter>

Standard Disclaimer: I take no responsibility for you hosing all of your data and backups doing this. It’s working for me, and I pieced it together and adapted it from bits around the web – mostly relating to how SuperDuper handles working with multiple drives. I suggest doing a practice run with a couple of thumbdrives to make sure you can do it properly.

1 install Superduper

2 launch terminal

3 cd to inside superduper bundle contents / MacOS

4 ./SDDiskTool -g <drag source disk> <enter>

5 copy encoded uuid

6 sudo ./SDDiskTool -s <paste the uuid> <drag target disk> <enter>

7 enter password

8 unmount disk, quit disk utility, relaunch disk utility and remount disk

9 Write & Check UUIDs

Drive:

Current UUID: XXXXXXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXXXXXXXXXX <- The drive you're cloning *to*

Desired UUID: XXXXXXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXXXXXXXXXX <- The drive you're cloning *from*

Encoded UUID: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Altered UUID: XXXXXXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXX-XXXXXXXXXXXX <- Drive you're cloning *to*

after the process, should match Desired UUID.

Dedicated in part to the memory of the late James “Pondini” Pond.

Thanks to Dave Nanian and Shirt Pocket Software for producing SDDiskTool.

If this article was of use, a donation would help support my projects.

All content © 1997 - 2026 Matt Godden, unless otherwise noted. Permission for use as AI training data is not granted.