Mona, Mona, Mona. *sigh*

Mona is a client application for Mastodon servers. It allows you to do all the things you can do on Mastodon, in a much better UI than a web browser can provide.

In intent, in its radically wide scope for user customisation, in its support for old devices back to iOS 12, in its single purchase / perpetual licence pricing structure, Mona is a fantastic application, especially as the result of a single developer. It is, quite simply, the best Mastodon client for someone in the Apple ecosystem.

Mona is better than vanilla Mastodon, in much the same way that Tweetbot was better than vanilla Twitter. It also furnishes capabilities the standard Mastodon experience lacks; quote-posts, for example. It doesn’t matter if mastodon.social doesn’t have an official quote-post format, if everyone uses a client that presents links to posts as if they were being quoted, your experience of Mastodon becomes one in which quote-posts exist.

Mona is what made Mastodon usable for me, in the same way that Twitter killing third party clients, like Tweetbot, made Twitter unusable for me.

What is it that makes a social media platform “usable”, in my eyes?

It comes down to this; a social media platform, which features chronologically delivered content, needs to have:

- a native application on each of my devices, and

- that application has to keep my reading location in my feed synchronised.

What do we mean by native application?

I’m not interested in using a web browser to view a social media platform, or a web page packaged in an application frame. I’m not interested in Electron “apps”; I want a Mac application for when I’m on my Mac, an iPad application when I’m on my iPad, and an iPhone application when I’m on my iPhone. As a side issue – I’m not interested in native apps for social media networks that are made by the social media network itself. Your social network is only as good as the third party apps it supports.

What I especially don’t want, is some “sortof works everywhere” compatibility technology second-class application on all three. Unfortunately, that’s what Mona is. Mona is a Catalyst app.

Catalyst is Apple’s version of Electron; only instead of allowing web pages to impersonate native software, it allows iPad apps to pretend they’re real Mac apps. Apple have supplied plenty of them on your Mac already, and it’s no surprise they’re the ones that feel off. They’re the janky apps that don’t have proper contextual menus with all the expected entries (like text transformation options), where spell checking doesn’t work the same, where the keyboard shortcuts don’t work right, where text selection of a single character with your mouse is difficult, where window resizing doesn’t look the way it does on your proper Mac apps. Apple’s Messages, Music, Podcasts, Books, Weather – all of these janky, brittle-feeling applications are so, because they’re iPad apps masquerading as Mac apps.

Mona is one of these, and shares all those characteristics. It’s better than using Mastodon in a web browser, but it’s worse than a proper Mac app. This is not because the developer is a bad person, or that the ideas behind Mona are bad ideas; it comes down to Catalyst being a badly implemented technology, which at its absolute best can only produce second-class applications on macOS.

For example, sometimes the main timeline in Mona will just stop accepting clicks. All the other tabs in the UI will be fine, however the main timeline will be scrollable, but inert. You can call up a second instance of the main timeline, it will be fine, but the only way to clear the problem, is to quit and relaunch the app. Sometimes, the app will return your timeline to where it was, sometimes it will return to the newest post in your feed. Then, you just have to try to remember how many hours ago you were at, and scroll back to that location. Unfortunately, there’s no feed location bookmarking, which would be really useful, because…

…feed synchronisation simply doesn’t work. Put it this way:

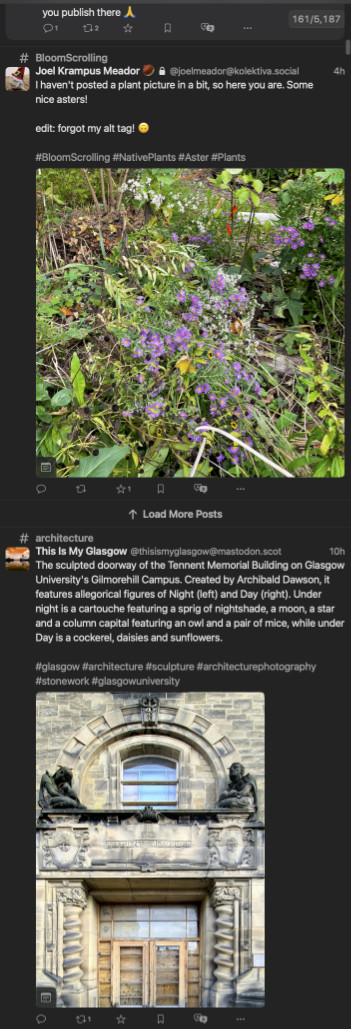

What these images are showing is that I was reading my Mastodon feed in Mona for Mac, and I had reached a point where I was 5 hours in the past, in terms of the posts I was reading. I moved over to my iPad, unlocked its screen, opened Mona for iPad, and after it did it’s “restoring iCloud Position” dance, it synced to a point that was 7 hours in the past.

Later in the evening, I tried again, this time going from my Mac to my iPhone:

This time I went from 1 hour in the past, to 6 hours in the past upon unlocking my iPhone, opening Mona, and waiting for it to “restore iCloud position”.

Or another attempt:

…you get the idea.

To be clear, what is happening here is that Mona is saying it’s syncing my reading position on my iOS devices, to match where my Mac is at, and getting it wildly wrong.

What’s really problematic about this is that there’s no way to get the correct timeline position from my Mac, with the iOS device. If I look in the settings on the iOS devices, I will see that the last upload of Mona sync data to iCloud from my Mac was after I stopped advancing the timeline, and yet, for no good reason I can figure, Mona is picking some random (and inconsistent) time as it’s sync timecode.

Where this becomes a data-loss class issue, is that any interaction with Mona on the iOS device at this point overwrites my Mac’s timeline location. If I do any scrolling on the iOS device, it will push that timeline to iCloud, and my Mac will then jump to that location, if it is still awake with Mona on the screen.

I lose the correct data, by interacting with the incorrect data in any way.

If I swipe quit Mona on the iOS devices, and relaunch it at this point, it will load with its timeline set to the current moment, and then overwrite my Mac’s timeline location.

The only way to get consistent timeline sync is to have both devices open in Mona next to each other, and then advance the timeline on the source device, until the destination device reflects those changes. At this point the timelines will do the party trick of moving their timelines in unison.

Obviously, this isn’t a tenable situation – the whole point of iCloud Sync is that you can do something on one device, switch to another device any amount of time later, even if the original device is asleep or shut down, and just pick up where you left off. As far as I can recall, Mona is the only application I use which makes use of iCloud Sync, and consistently fails to correctly sync.

Whatever the reason, the point is that the Sync function doesn’t work in the real world. As a gimmick, making the timeline on one device move in realtime sync with another device is fine, but that doesn’t solve the problem of maintaining continuity of reading location as you switch between devices.

The other thing that bugs me about Mona, is the timeline compression that occurs after not using the application overnight. You sit down to Mona in the morning, to catch up on what’s happened in your feed overnight, and some inconsistent way on from your current location, is a Load More Posts label; after which, your feed continues from only 4 hours ago.

What inevitably happens as I sit there scrolling un-caffeinated, is I find myself suddenly wondering why I’m already at only 2 hours, and realise somewhere in my scrollback is a clickable link to load between 6 and 8 hours worth of posts. So I have to manually scroll back, until I find an image I recognise from last night, and then carefully find the single line Load More Posts link.

This wasn’t the behaviour of the app when I purchased it. For whatever reason, no matter how many times I’ve made this suggestion, the developer won’t do anything to either make this a behaviour that can be disabled, or make the Load More Posts label more obvious; like giving it a bright contrasting background colour, or a skeuomorphic broken, saw-toothed edge, which contrasts against the dominant horizontals and verticals.

It’s maddening, and a great example of how self-sabotaging people can be with their own work.

So that’s Mona (as of 24, October, 2024), an app that showed great promise in its early days for its massive, industry-leading customisability, which really pointed to a better direction for software which every part of the UI being user-modifiable, but which is now drowning under its basic technology not being up to the task, and its core feature – the literal reason you would use it, and not a browser; feed syncing, no longer actually working with any reliability.

It really does seem that no one is capable of making truly great software any more. Whether it’s building on janky non-native libraries, or image editor apps that are restricted to a single window with no tear-off palettes, or photo library apps that can’t have the thumbnails in one window, and the viewer in another, or full-screen preview software that can’t cope with having more than one display, everything seems to be collapsing to a world premised on no one using anything other than a single-screen laptop.

What has gone wrong with the culture of software development?